Identity area

Reference code

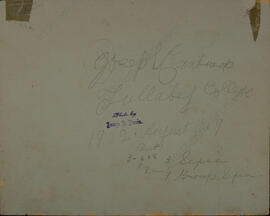

Title

Date(s)

- 1818-2010 (Creation)

Level of description

Extent and medium

20 boxes

Context area

Name of creator

Administrative history

The Society of Jesus was founded in 1540 by Ignatius of Loyola and since then has grown from the original seven to 24, 400 members today who work out of 1,825 houses in 112 countries. In the intervening 455 years many Jesuits became renowned for their sanctity (41 Saints and 285 Blesseds), for their scholarship in every conceivable field, for their explorations and discoveries, but especially for their schools. The Society is governed by General Congregations, the supreme legislative authority which meets occasionally. The present Superior General is Father Arturo Sosa. Ignatius Loyola was a Spanish Basque soldier who underwent an extraordinary conversion while recuperating from a leg broken by a cannon ball in battle (see picture). He wrote down his experiences which he called his Spiritual Exercises and later he founded the Society of Jesus with the approval of Pope Paul III in 1540.

From the very beginning, the Society served the Church with outstanding men: Doctors of the Church in Europe as well as missionaries in Asia, India, Africa and the Americas. Men like Robert Bellarmine and Peter Canisius spearheaded the Counter Reformation in Europe, courageous men like Edmund Campion assisted the Catholics in England suffering under the terrible Elizabethan persecutions and missionaries like deNobili Claver, González, deBrito, Brebeuf, and Kino brought the Gospel to the ends of the earth. No other order has more martyrs for the Faith.

Ignatius Loyola had gathered around him an energetic band of well-educated men who desired nothing more than to help others find God in their lives. It was Ignatius’ original plan that they be roving missionaries such as Francis Xavier, who would preach and administer the sacraments wherever there was the hope of accomplishing the greater good. It soon became clear to Ignatius that colleges offered the greatest possible service to the church, by moral and religious instruction, by making devotional life accessible to the young and by teaching the Gospel message of service to others. From the very beginning these Jesuit schools became such an influential part of Catholic reform that this novel Jesuit enterprise was later called “a rebirth of the infant church”. The genius and innovation Ignatius brought to education came from his Spiritual Exercises whose object is to free a person from predispositions and biases, thus enabling free choices leading to happy, fulfilled lives.

Jesuits were always deeply involved in scholarship, in science and in exploration. By 1750, 30 of the world’s 130 astronomical observatories were run by Jesuit astronomers and 35 lunar craters have been named to honor Jesuit scientists. The so-called “Gregorian” Calendar was the work of the Jesuit Christopher Clavius, the “most influential teacher of the Renaissance”. Another Jesuit, Ferdinand Verbiest, determined the elusive Russo-Chinese border and until recent times no foreign name was as well known in China as the Jesuit Matteo Ricci, “Li-ma-teu”, whose story is told by Jonathan Spence in his 1984 best seller. China has recently erected a monument to the Jesuit scientists of the 17th century – in spite of the fact that since 1948 120 Jesuits languished in Chinese prisons. By the way, no other religious order has spent as many man-years in jail as the Jesuit order.

Jesuits were called the schoolmasters of Europe during the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, not only because of their schools but also for their pre-eminence as scholars, scientists and the thousands of textbooks they composed. During their first two centuries the Jesuits were involved in an explosion of intellectual activity, and were engaged in over 740 schools.

Then suddenly these were all lost in 1773. Pope Clement XIV yielding to pressure from the Bourbon courts, fearing the loss of his Papal States, and anticipating that other European countries would follow the example of Henry VIII (who abandoned the Catholic Church and took his whole country with him), issued his brief Dominus ac Redemptor suppressing the Society of Jesus. This religious Society of 23,000 men dedicated to the service of the church was disbanded. The property of the Society’s many schools was either sold or made over into a state controlled system. The Society’s libraries were broken up and the books either burned, sold or snatched up by those who collaborated in the Suppression. As if unsure of himself the Pope promulgated the brief of suppression in an unusual manner which caused perplexing canonical difficulties. So when Catherine, Empress of Russia, rejected the brief outright and forbade its promulgation, 200 Jesuits continued to function in Russia.

That Jesuits take their special vow of obedience to the pope quite seriously is evident from their immediate compliance with distasteful papal edicts. Clement XIV’s Suppression is one example. Another occurred earlier in 1590 when Pope Sixtus V wanted to exclude Jesus from the official name of the Society. Jesuits immediately complied and offered alternate names but Sixtus died unexpectedly before his wish could be carried out. Included among these occasional papal intrusions in the Society’s governance was Pope John Paul II’s appointment of a delegate to govern the Society during Superior General Arrupe’s illness. So edified was he at the Society’s immediate compliance that the pope later lavished extraordinary praise on the Jesuit Order.

The Society was restored 41 years after the Suppression in 1814 by Pope Pius VII. Although many of the men had died by then, the memory of their educational triumphs had not, and the new Society was flooded with requests to take over new colleges: in France alone, for instance, 86 schools were offered to the Jesuits. Since 1814 the Society has experienced amazing growth and has since then surpassed the apostolic breadth of the early Society in its educational, intellectual, pastoral and missionary endeavors.

They form a Jesuit network, not that they are administered in the same way, but that they pursue the same goals and their success is evident in their graduates, men and women of vast and varied talent.

Repository

Archival history

Material collected by Irish Jesuits.

Content and structure area

Scope and content

The Jesuits bought Tullabeg in 1818 (dedicated it to St Stanislaus) and opened a preparatory school for boys destined to go to Clongowes Wood College, Kildare. St Stanislaus College gradually developed as an educational rival to its sister school. It merged with Clongowes Wood College in 1886. Tullabeg then became a house of Jesuit formation: novitiate (1888-1930), juniorate (1895-1911), tertianship (1911-1927) and philosophate (1930-1962). In 1962, it was decided that the students of philosophy should be sent abroad for study. Tullabeg subsequently became a retreat house and was closed in May 1991.

The papers of St Stanislaus College include information on a history of the area around Tullabeg, building and property (1912-2004), correspondence with Superiors (1881-1971), finance (1912-1990), documents on Jesuit training (1818-1962), retreat house (1949-1960) and artworks (1940-1991).

Material is in the form of letters, reports, architectural plans, notes, maps and photographs (1902-1990). Programmes for plays include Shrovetide at St. Stanislaus College, Tullamore; ‘The Man with the Iron Mask’, ‘All at Coventry’ and ‘The Smoked Miser’ (1885) and for ‘Caitlín Ní Uallacáin’ and ‘Cox and Box’ and details Jesuits who performed (1925).

Appraisal, destruction and scheduling

All items retained permanently.

Accruals

None.

System of arrangement

Material was catalogued in 1999, with some additions in 2004, 2006, and 2013.

Conditions of access and use area

Conditions governing access

The Irish Jesuit Archives are open only to bona fide researchers. Access by advance appointment. Further details: www.jesuitarchives.ie or [email protected]

Conditions governing reproduction

Photocopying is not available. Digital photography is at the discretion of the Archivist.

Language of material

Script of material

Language and script notes

Physical characteristics and technical requirements

Finding aids

Printed finding aid available.

Allied materials area

Existence and location of originals

Irish Jesuit Archives, 37 Lower Leeson Street, Dublin 2

Existence and location of copies

Related units of description

Clongowes Wood College maintains its own archives. Contact: Clongowes Wood College, Clane, county Kildare.

Publication note

Byrne, Michael, 'Tullabeg, Rahan Tullamore 1818-1991', Offaly Heritage 2, 2004, pp90-111.

Publication note

Corcoran, Fr Timothy SJ, 'The Clongowes record, 1814 to 1932: with introductory chapters on Irish Jesuit educators, 1564 to 1813', Dublin: Browne and Nolan, 1932.

Publication note

Costello, Peter. 'Clongowes Wood: A history of Clongowes Wood College 1814-1989', Dublin: Gill and MacMillan, 1989.

Publication note

Finegan SJ, Fr Frank, ‘Tullabeg (Rahan) 1818-1968’, Jesuit Year Book, 1969, pp5-24.

Publication note

Grene, Fr John SJ, ‘A contribution towards a history of the Irish Province of the Society of Jesus, Memorials of the Irish Province, S. J. Centenary Year 1814-1914', parts I & II. Dublin: O'Brien & Ards, 1914.

Publication note

Laheen, Fr Kevin A SJ,

'The Jesuits in Tullabeg: The Early Years From Mission 1810 to Province 1860', O’Brien Publications, 2007.

'The Jesuits in Tullabeg: A Century of Service 1814-1914', O’Brien Publications 2009.

'The Jesuits at Tullabeg 1817-1991: The Final Curtain 1991', O’Brien Publications, 2010.

Publication note

Nerney, Fr Denis SJ (ed.), 'Notes on the history of the Tullabeg district'.

Publication note

'St. Stanislaus' College, Tullabeg, King's County : a college (1818 to 1886); Noviceship and House of Studies (since 1888) of the Irish Province of the Society of Jesus', Society of Jesus, 1910.

Publication note

Wrafter, Sister Oliver, 'Rahan Look Back', Naas: Leinster Leader, 1989.

Notes area

Alternative identifier(s)

Access points

Subject access points

Place access points

Name access points

- St Stanislaus College, Tullabeg (Subject)